Dear America and Canada, some advice for social enterprise. Best wishes, the UK

Liam Black reflects on roles of government and accountability in social enterprise following “The Social Entrepreneur’s A to Z” book tour. With the generous and

Liam Black reflects on roles of government and accountability in social enterprise following “The Social Entrepreneur’s A to Z” book tour. With the generous and

The Trico Charitable Foundation and the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) have joined forces to boost support for Canada’s leading social enterprises. As a

Written: by Liz Weaver, Vice President – Tamarack, an Institute for Community Engagement Revised on January 26, 2015 By now we know that collective impact

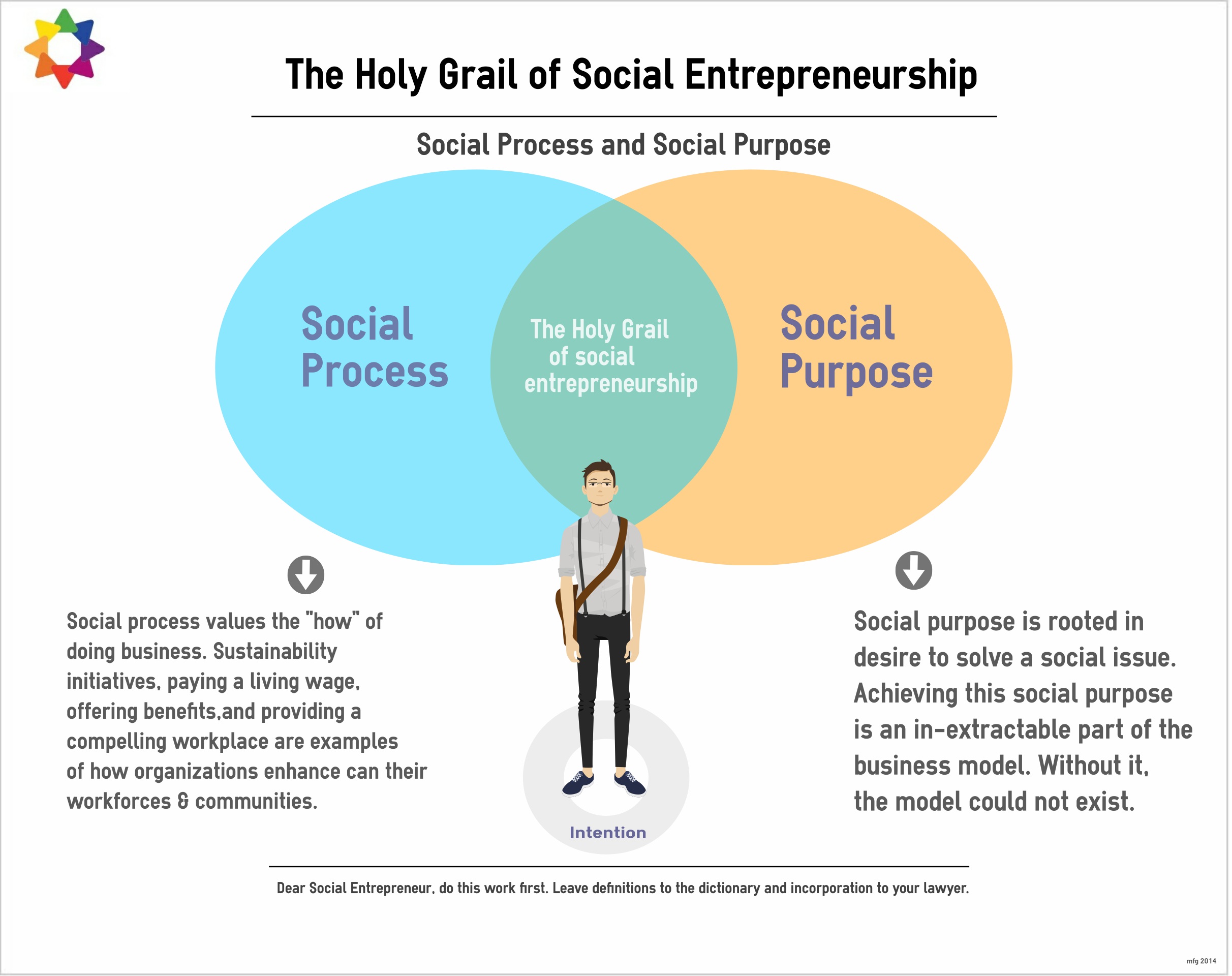

We’re often asked for our definition of social entrepreneurship.

In the past three years, our answers have morphed. We started purely on the non-profit side, but encountered problems whereby “everyone” was becoming a social entrepreneur. As we shifted toward the for-profit side, we started to rub up against CSR and social-washing concerns. Instead of broadening our ability to discuss the possibility of social entrepreneurship, we found ourselves increasingly walled within incorporation definitions.

A long time ago, I argued for our ability to hold the broadest definition of social entrepreneurship that we possibly could – so that we might experience and learn from the models holding the greatest yields. And yet, over time, I have found myself sniffing for flaws in business model construction.

“Is that really social impact?”

“Is selling to government actually a market opportunity?”

“Does receiving a subsidy take away the sparkle of the idea?”

Last spring, I joined the Futurpreneur Canada Action Roundtable in Calgary to discuss the needs of advancing entrepreneurship across the country. I listened to entrepreneurs describe their dedication to the community, to their employees, and to creating an organization that was more than just about business (that was about more than just business). They talked about living wages, volunteer days, health benefits, professional development, community engagement, and employee ownership.

When asked as to whether these elements equaled social entrepreneurship, my gut was no, but my head kept asking “why not”? In short, social change was not the goal.

However, when I have looked at social enterprise models with social as the goal, often I am confounded by the use of volunteers or beneficiaries as “staff” or government as the sole purchaser. There may well be social purpose to these organizations, but they lack the elements described above – the social process.

Social process: Values the “how” of doing business. Sustainability initiatives, paying a living wage, offering benefits, and providing a compelling workplace are examples of how organizations can enhance their workforces and communities.

Social purpose: Roots itself in the desire to solve a social issue. Achieving this social purpose is an in-extractable part of the business model.

Without it, the model could not exist.

Unpacking these concepts required us to start from one vantage point, not definitions, not incorporations, not business models, but rather from “intentionality”.

If we started back at square one, at the point of intention, how should a social entrepreneur start building their business model.

The mantra for transformative change has become ubiquitous. After all, who would opt for treating symptoms, often derisively labeled as band-aids, over striving for a cure? While the clarion call of transformation also beckons for us, we’re concerned by a dynamic emerging between individuals taking community action because they saw a “simple” need (kids need shoes, women shelters need soup) and the analysis of those actions by those who call for transformative change. Whether these interventions come through the lens of philanthropy, humanitarianism, or economic development and regardless of whether they are individual actions or those taken by organizations, we risk losing much by judging all social initiatives against the standard of transformation.

The harsh reality is new ways of doing things in an old system typically yields old results. It’s akin to planting a flower in the middle of a desert. Embracing the recommended core disciplines (‘action’, ‘learning’ and ‘leveraging’), guided by new mindsets (‘co-creation’, ‘electric judo’ and ‘systems health’) and an ecosystems approach presents the best chance of producing the culture change we need, serving the goals of the government, and maximizing the potential of the SIE for all Albertans.

Perhaps the crux of the matter was addressed in one question within the consultation documents: “How can we leverage ALL types of innovation?”

The acronym for “action”, “leveraging” and “learning” added to “innovation” could be “ALL Inn.”

This could be Alberta’s rallying cry and represent:

• Innovation will be everywhere.

• Innovation includes everyone/everyone has a role.

• Alberta is committed to the innovation agenda.

We applaud the Alberta Government for taking the bold step of creating a Social Innovation Endowment. As a partner in this work, we see ourselves as accountable for doing all we can to ensure the success of the SIE in Alberta and championing its future. We believe that Government should hold the social innovation sector to high account as a partner in this work and empower it to do the work needed so that all Albertans may benefit from the opportunities that social innovation holds.

If the SIE is to achieve its ambitious, arguably audacious, goal of solving ‘wicked problems’, Alberta will have to go “ALL Inn.”.

As a small and relatively new private foundation, we were intrigued by Kania, Kramer & Russell’s discussion of an emergent philanthropy framework. While our initial debates focused on the ‘newness’ and the key elements highlighted in their article were theoretically interesting, we were more attracted to the ‘how to’ elements outlined in the ‘How to move to an emergent model’ section.

For us, the authors’ move away from their views on strategic philanthropy does not mean that emergent philanthropy loses its own requirement to be strategic. Rather, it honours the notion that the shift from predictive to emergent models requires different processes, communication and cultures to ensure that we can describe the impact of what we are doing.

To this end, the ultimate potential of the article lies in its attempt to explain how emergent philanthropy can be done. Sadly, this does not seem to be the focus of much of the discussion that has occurred. This strikes us as a squandered opportunity. Imagine the incredible value of all the organizations that participated in this debate talking about ‘co-creating strategy’, ‘working the attractors’ and ‘improving system fitness’ – do they embrace these elements, what has worked, what hasn’t, what have they learned? We are sharing our story in the hopes that it inspires more experienced foundations to join a discussion of the ‘how to’ aspects of the article.

At its core, social enterprise embodies two elements: the passion for addressing social challenges and the generation of market-based revenues in support of that social purpose. Regardless of whether the social enterprise is an individual or an organization, regardless of their choice of incorporation – non-profit or for-profit, these two elements are the driving force.

Those two elements aren’t just identifiers. It is the conjunction of those two elements, bringing together the power markets and social purpose, which is at the heart of the incredible promise of social enterprise. While it has always been assumed that business activity produces an indirect benefit to its community (e.g. through employment and tax revenue), social enterprise brings the power of ‘social’ more deeply into the business world, daring to ask what profits could be made and advances could be achieved if businesses embedded in their value propositions a commitment to directly solve the world’s biggest and most perplexing social challenges. For social organizations, social enterprise brings the power of markets to make them more financially sustainable and take their social impact to the next level.